This is the 10th blog in our Examining Climate series, where CCJ staff members and others will be sharing their favorite (or least favorite) climate solution, looking at the benefits and the costs in the hope of sparking an honest conversation about how we address the climate crisis and keep our focus on environmental justice. This blog was written by CCJ Events Coordinator Sarah Sweeney.

When I was growing up in rural Greene County, the idea of climate change and what it really meant couldn’t have been further away from my mind. I had no context outside of the basics of my science classes: “Fossil fuels are non-renewable resources” was something we heard time and time again, and you best believe in a coal mining community there was buzz around that sentiment. But what did it all really mean? I heard chatter about things like the ozone layer and global warming, and as I got older I heard heart-wrenching stories of the melting of the ice caps and stranded polar bears. These things were all awful, but at the time, it didn’t feel like it touched my life much in a little farming community in Greene County.

As I grew up, I learned we actually had been talking about climate all along. The language of climate change was very different for those of us in rural America. Instead of talking about methane emissions or air pollution, we would say things like, “Boy, the spring flowers are popping up earlier and earlier,” or “It was such a dry year. My tomatoes did terrible,” or perhaps you heard someone mention, “It sure doesn’t snow like it used to.” I had even begun to hear exclamations like “Can you believe I found a tick in January!?”, when in previous years ticks died off in the winter months.

I am an adamant believer that we never quit learning, and as I learned more and more about climate change, there was one path towards climate solutions that resonated with this country girl again and again: native-led climate solutions.

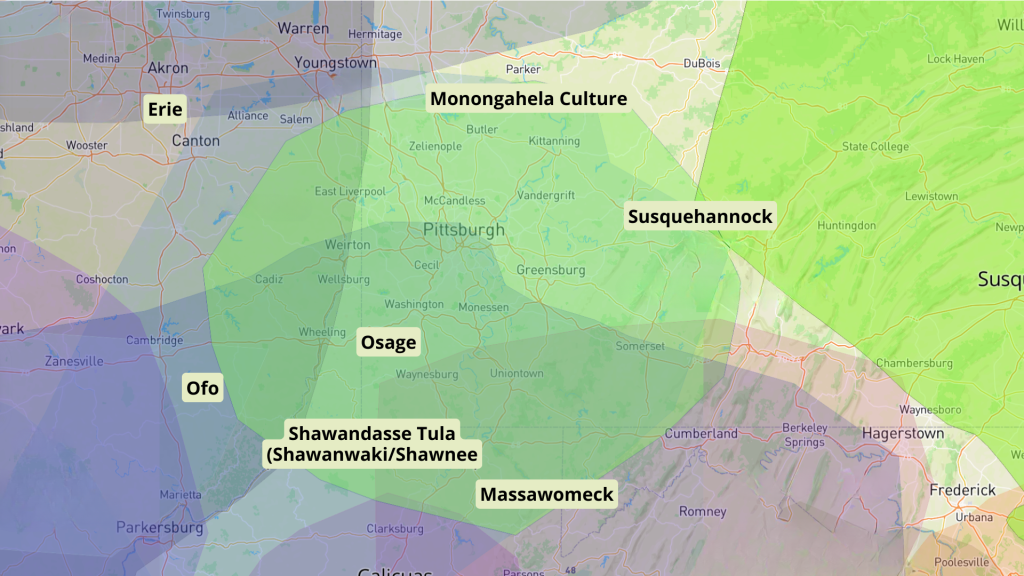

You might ask yourself, what’s the connection here? (Other than the fact that we are residing on the indigenous land of the Susquehannock, the Lanape, and the Delaware.) We know that climate change doesn’t affect all communities equally, and that rural and Indigenous peoples are some of the groups who will be most affected. According to US census data, 20% of Americans live in rural areas. However, according to the First Nations Development Institute, 54% of all Indigenous Americans live rurally. (Please note: due to outdated census definitions and poor data quality, there may be an even more significant portion of Indigenous Americans living in these areas.)

Much like many rural people struggling to make ends meet throughout history, Indigenous Americans have contributed very little statistically to what fuels climate change. Yet, they are one of the groups that suffer the most. Often overlooked politically, rural Americans of all backgrounds find themselves disproportionally affected by the consequences of climate change, such as vulnerability to extreme weather and food security challenges. Not only do they carry the weight of having communities often at the front lines of extractive industry, but they also have to work in some of the most hazardous environments to be able to keep food on the table for their families, which leaves little time for fighting for political policy that could benefit them.

As I read further, the ideas that Native leaders have put forth felt so grounding to me. They just make sense. Native climate solutions are intuitively based on natural principles. They inherently value land, water, and earth in a very intimate way, and embrace a circular way of living meaning they give back as much if not more than they take from the environment because we are all connected. With traditional knowledge and wisdom of the environment, Indigenous Americans offer traditions that are the guidebook to how we can build a more climate-resilient society. For example, indigenous traditions care for forests and marshlands, both of which are natural carbon sinks. A carbon sink is an area that stores more carbon than it emits into the earth’s atmosphere, essentially removing excess carbon from the atmosphere. In a sense, forests and marshlands are the original carbon capture technology. Protecting and properly managing these areas is essential in our battle to mitigate the harmful effects of climate change. Indigenous people are stewards of around 36% of the world’s intact forests. When Indigenous peoples’ ancestral lands are protected and it is ensured that they can remain the caretakers of these lands, we are also fighting climate change and protecting these green spaces.

This balanced way of looking at nature is so relatable for me. Growing up, my dad always had a grounded way of looking at what we took from and gave back to the land around us. For example, if you pick berries, make sure some go to seed. Take what you need, but never more. My dad was and is a big morel mushroom hunter (he would never call himself a forager), not for any distaste towards the word – but simply because it wasn’t a part of the regions dialect. Hunting itself was in my childhood, an ingrained part of our cultural identity. To this day, he keeps a little booklet where he records his yearly yields, their location, the time of year, and much more. From years of growing up in the country, he intuitively senses slight changes in the natural landscape.

Before colonization, Native peoples managed wooded areas with controlled burns. From Hawaii and all across North America, this was a common practice. These burns not only encouraged the growth of particular plants, improved soil quality, and served to cut off the fuel supply that often fuels massive wildfires like those we have seen in recent years. You may know these cultural burnings as prescribed burns. Though slightly different in intention, cultural- and federally-sanctioned prescribed burns often have similar outcomes when it comes to their climate impact. Not only do these burns support controlling the spread of wildfires, they also increase production of fruiting trees and plants like the chestnut in the east and blueberries in the Great Lakes region. The natural systems of biology, ecosystems, and life are built on the uninterrupted progression of success and finding a place in this complex web of relationships. Fires had a place in that relationship, and with its removal from those ecosystems, many interdependent relationships fell apart. One such unexpected relationship was the effect of control on unintended pests or invasive species. They are foreign to a fire regime and, therefore, do not have the ability to flourish in ecosystems that still have regular fires, while the natives thrive. These natural systems not only continue to offer the best solutions to climate change but also offer the most efficient solutions to many of the human-induced issues ecosystems are battling today.

I have myself lived through two wildfires. In my early 20s I moved to Durango, Colorado where I lived through both the Lightner Creek fire and the notable 416 Fire which, as of the writing of this article, currently sits as the 9th-largest wildfire in Colorado history. I can truly say it is indescribable to walk out your front door and smell the smoke before it has been officially announced a wildfire has started. That is exactly what happened when the Lightner Creek fire began. Once it was officially announced, my then-fiance and I hiked up a nearby peak and I sat down with my camera, taking photos of the rising smoke. I noticed a discrepancy in the photos and I thought it was a light flare caught on the photo. On closer inspection, I came to find I had captured the moment the flames had jumped to the closer side of the mountain. It is one of the moments in my life where I can say I truly was in awe.

The following year, my fiance and I hiked into the area of the Lightner Creek Fire. I took photos of what I saw. Amidst all the blackened tree bark was an overwhelming sight of lushness, of green.

As our policy makers continually drop the climate ball, fires like these have become more commonplace and all the more devastating. At one point in time, Native American cultural burns were outlawed in coordination with other legislation that harmed Indigenous tribes, but eventually the government walked back that legislation as they came to see the value in these burnings.

Much like the farmer who has built his livelihood on knowing what to grow in what season, how to look to the sky to read the incoming weather, and learning the habits of the animals that surround their farmland, Indigenous Americans have relied on the land and understanding even the most subtle changes within it for generations. Unlike some non-native folks however, Indigenous people have always lived with the knowledge that the wellbeing of humans and our shared planet are interconnected. When we protect our planet, we are also protecting ourselves and future generations. These are just a few examples of some of the ways Indigenous people are combatting climate change. Sometimes, the best course of action is to listen, learn, and pass the lead to those who know what to do with it. I believe in a cooperative climate future where we ALL work to be better stewards of our shared lands.