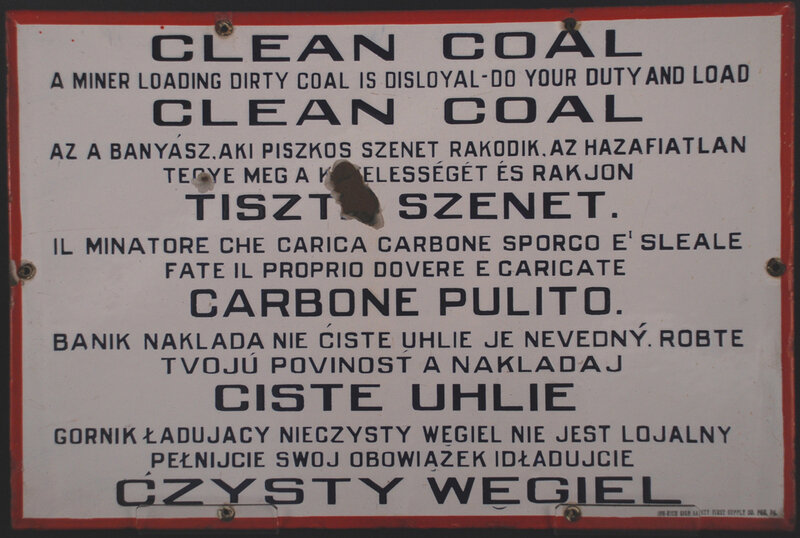

I grew up in the shadow of coal mining in Appalachia. The remnants of the industry were ghosts in my life. I often bike on the Montour Trail where the Montour Railroad used to take coal to the steel mills in Pittsburgh. After my bike rides, I sometimes get ice cream in what used to be the mine company store. Now on the trail I pass new hydraulic fracturing well pads being built to capture the natural gas trapped in the area’s incredibly valuable Marcellus Shale deposit. The economically depressed small, rural towns in my area were towns built by the coal companies. The headquarters of numerous oil & gas and coal companies are in a shiny office park next to my house. Every day on my way to work I pass unmarked trucks hauling potentially hazardous liquid waste from the well sites. A few years ago I looked up old mine maps and realized in shock that virtually all of the land that I grew up on been mined at one point. My connection to the coalfields is so deeply embedded into my life that it felt almost invisible to me until I brushed the dust off my great-grandfather’s union poster and dug into the history of the coalfields.

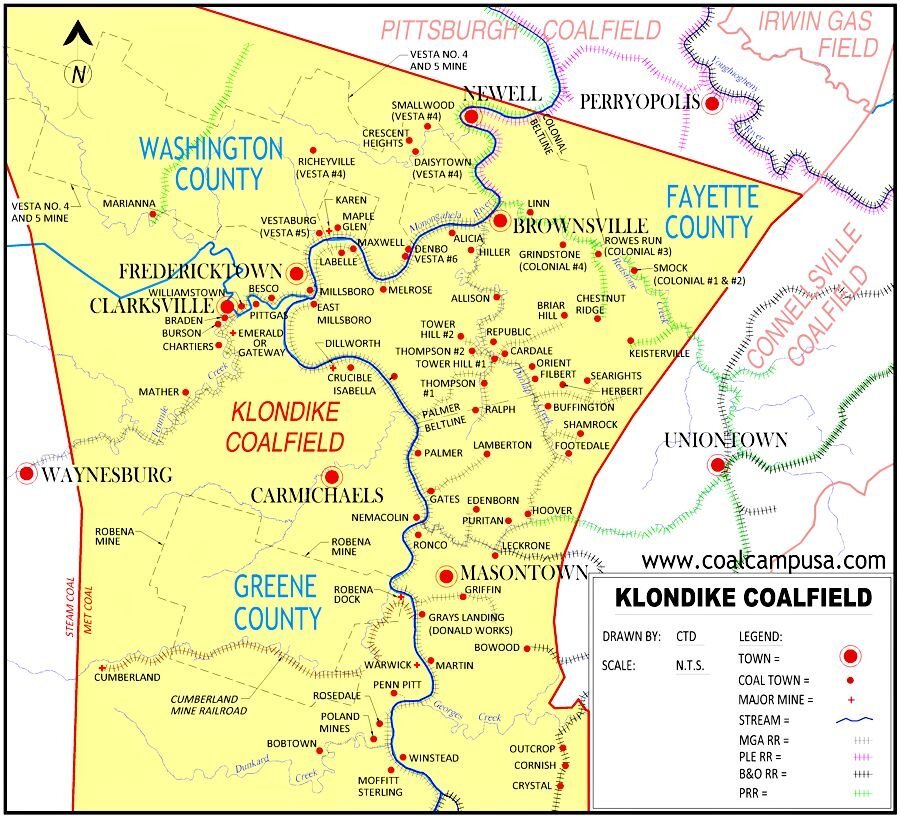

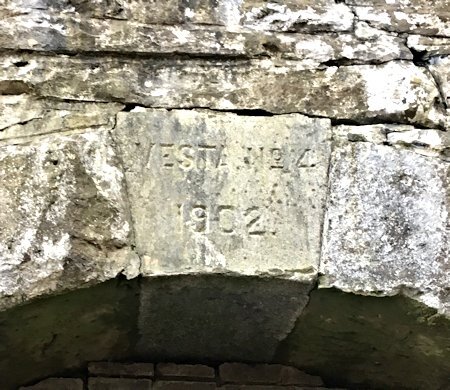

My great-grandfather, John, worked in the Vesta No. 4 mine in Daisytown, Pennsylvania his whole life. So did his father, who came from Lithuania. So did his father-in-law, who came from Hungary. The opportunities in my life today are built on their hard work in that mine. They all worked hard to achieve the so-called “American Dream” of a middle-class life for my family. Much of what prosperity and wealth is in our area is built on natural resource extraction and industry. The prosperity of America is built on the backs of our coal miners, past and present. Fossil fuels and steel are what built the 20th century. While that fossil fuel era needs to end as quickly as it started in order to prevent catastrophic levels of climate change, coal still represents 27% of our electricity generation (much of it still coming from Appalachia), and natural gas (also plentiful in this region) makes up an increasing 35% of electricity generation (as of 2018). Yet in the same vein, many issues in the area such as poverty, environmental destruction, and social injustice are related to these industries and what they leave in their wake. Appalachia has what is known as the “resource curse.” We live in an area rich in natural resources, but have less economic growth, less democracy, and unfavorable development outcomes. The resource curse is especially prevalent in areas with weak social institutions, which allows wealth to be concentrated in the hands of the powerful few. Whether we need an economist to give it a name or not, we know it to be true. We have seen the effects of the downturn of coal, steel, and other industries on our local economy. We have seen the health effects of pollution on our neighbors. We have seen the hard workers laid off before they could receive their pensions. We have seen natural gas extraction in our region provide some jobs and royalties but also pollute our air and waterways. While coal mining has moved towards bigger and more efficient mines deeper in Appalachia, natural gas continues to rapidly expand in Washington County. The farm where my grandma lives has been mined for coal, drilled for oil, and now “fracked” for natural gas. Whether under a different guise or not, the injustices that faced coal miners in past generations in Appalachia are still happening. The corporate greed that has ravaged our area is still alive and well today.

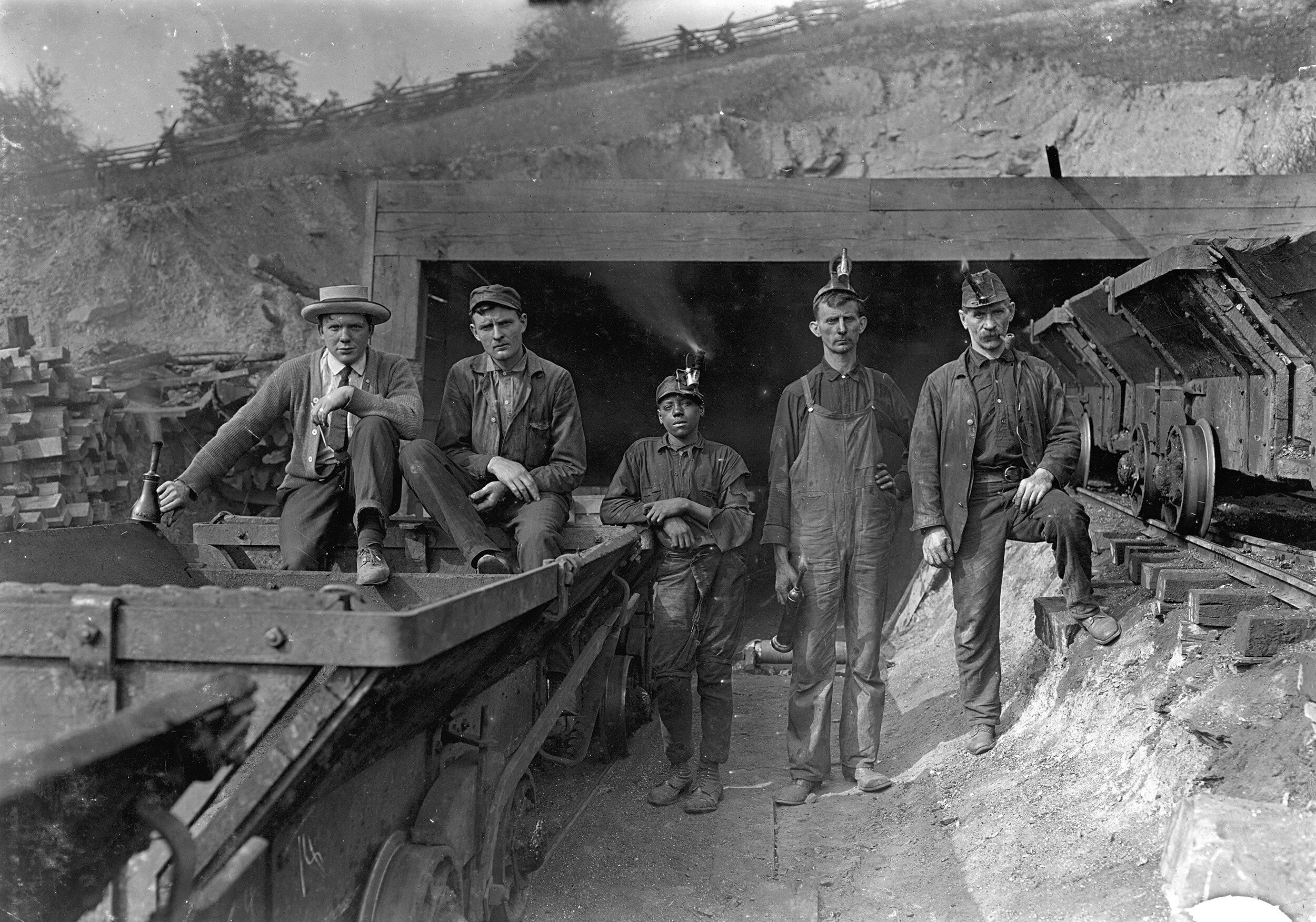

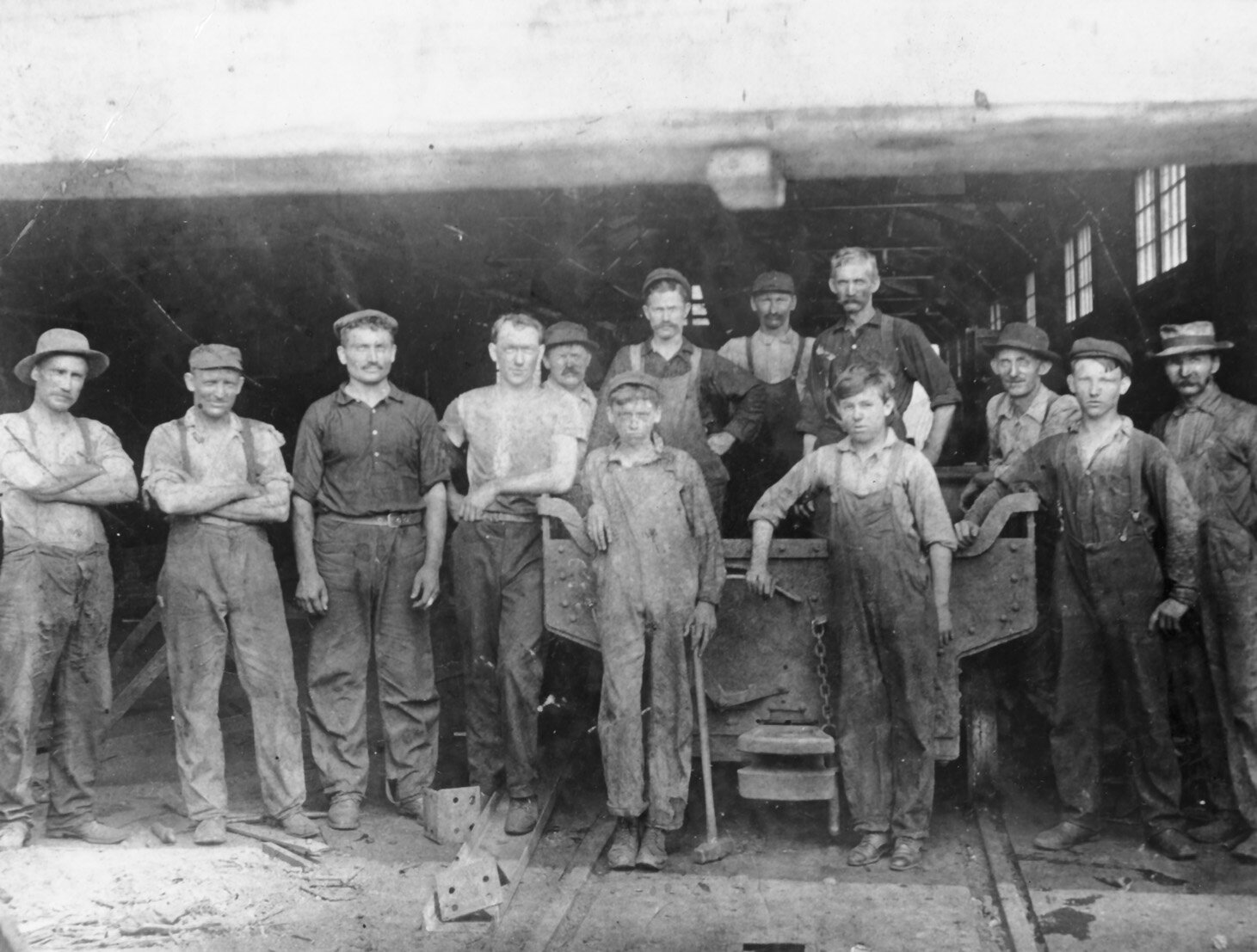

Coal mines in front of mine entrance in Red Star, WV, 1908

Source: Library of Congress

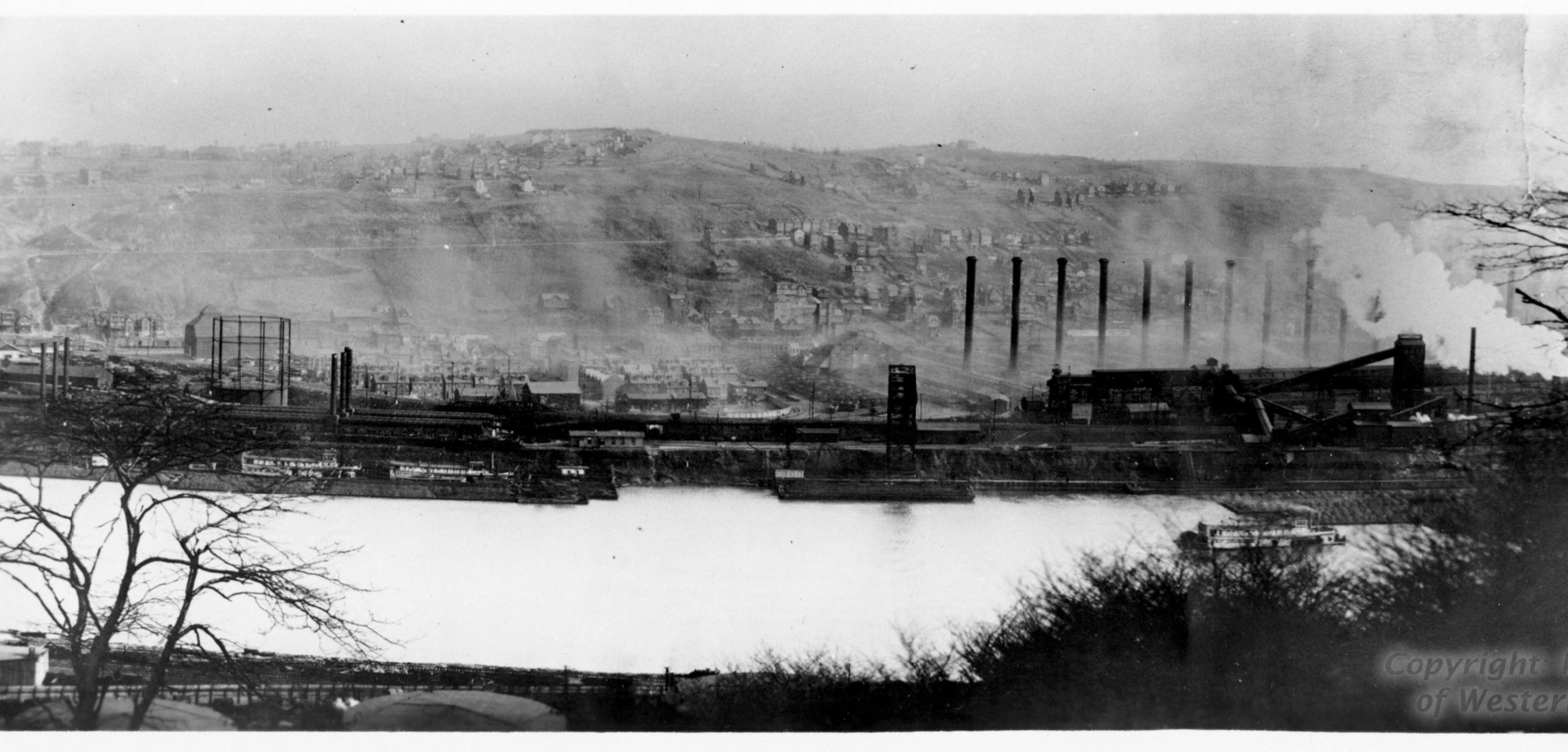

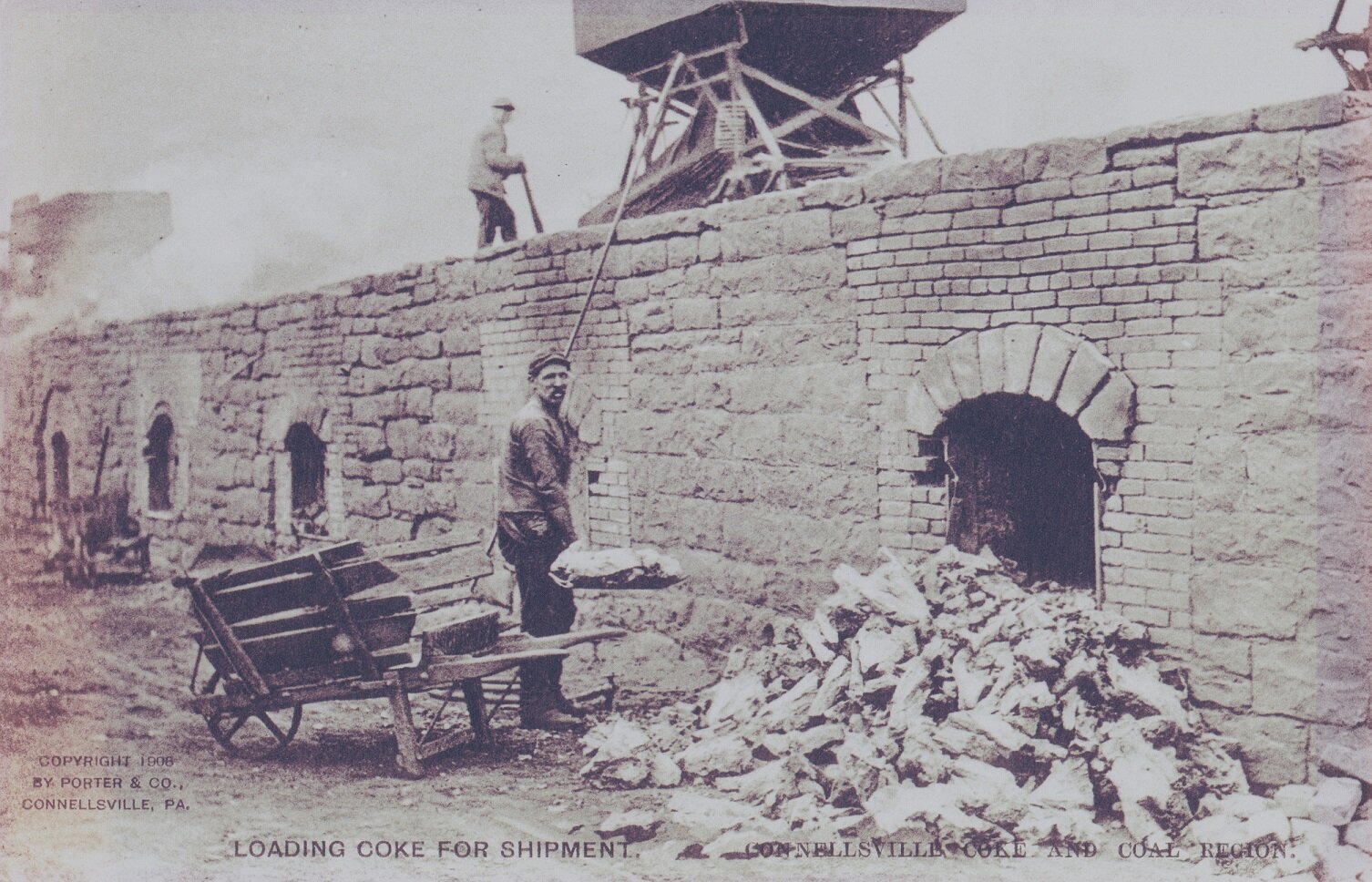

In 1762, Mt. Washington (which used to be called Coal Hill) was mined to supply Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh, with coal. This Pittsburgh Coal Seam was regarded as the most valuable industrial mineral deposit in the US, as the makeup of the coal was perfectly suited for making steel. Pittsburgh’s rivers, coal, and immigrant workforce made it the leading industrial powerhouse of the 19th and 20th century. The nickname of this era in Pittsburgh was the “Golden Age of King Coal, Queen Coke and Princess Steel.” At the same time, in 1868 James Parton wrote in The Atlantic that Pittsburgh “looked like hell with the lid taken off.” British novelist Anthony Trollope similarly wrote that Pittsburgh was “without exception…the blackest place which I ever saw.” According to Historic Pittsburgh, many people believed (or were told to believe) that “…high smoke output indicated high productivity…many people felt that coal smoke was good for the lungs and helped crops grow.” Pittsburgh was the epitome of industry and capitalism with virtually no environmental regulation or protections of workers’ rights.

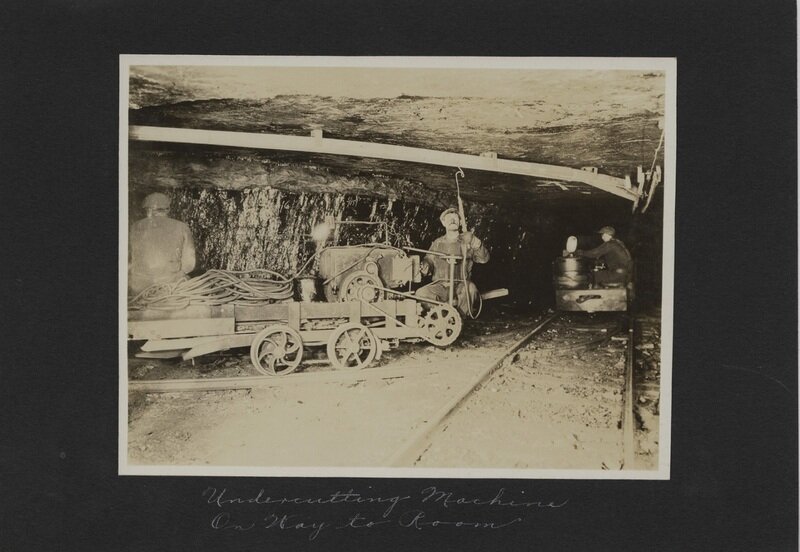

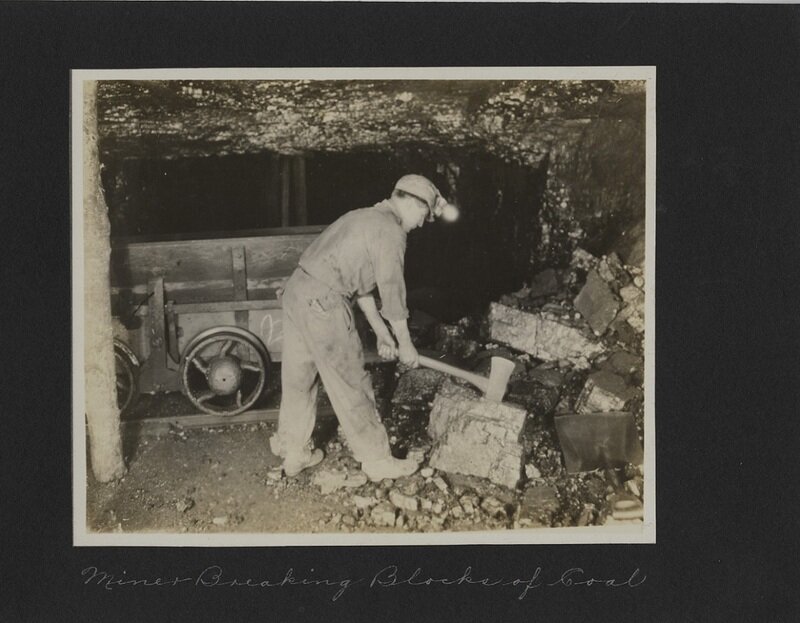

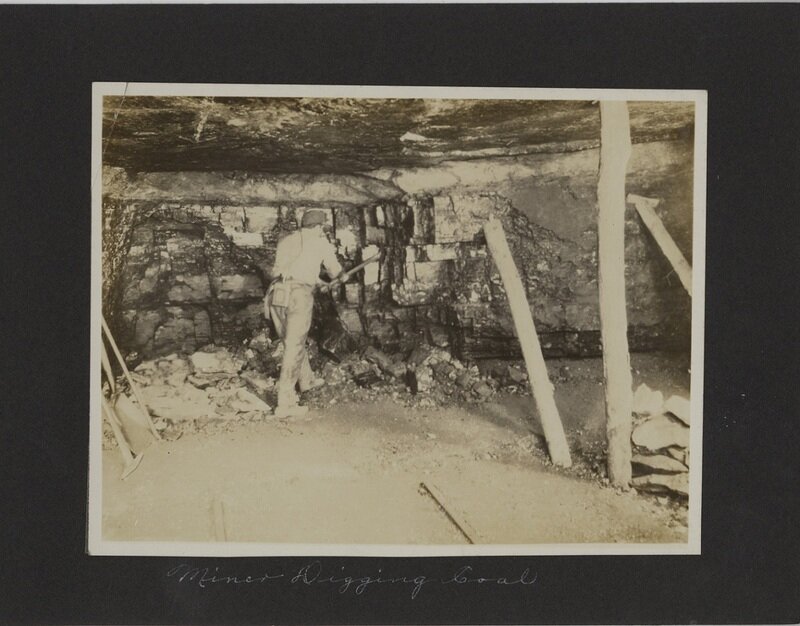

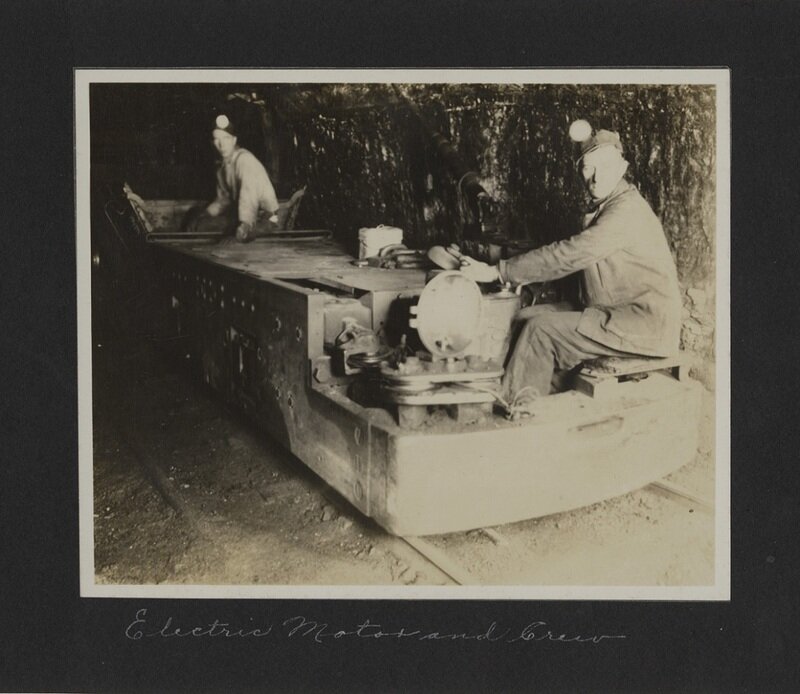

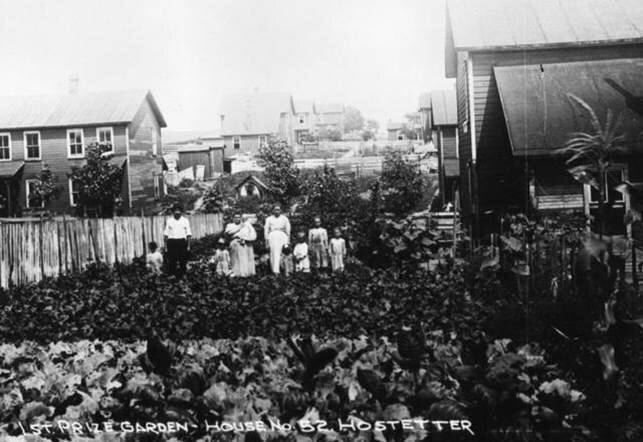

Meanwhile, immigrants were flocking to the coal patch towns in search of work and opportunity. According to the book “Always in a Hole” by Arthur Vincent Ciervo, “A strong body and a willingness to work hard . . . were much in demand, in particular, in the rapidly growing coal and steel industry. The skilled positions were filled by men who had learned their jobs in the anthracite mines of England, Wales, and Pennsylvania. Not enough Americans, however, were willing to undertake the difficult and dangerous work of digging and shoveling coal.” My own family members came from Lithuania and Hungary in search of work and a better life. They settled south of Pittsburgh in the Klondike Coal fields near the Monongahela River. The coalfields were so named as an allusion to the Alaskan Gold Rush. They worked in the same mine, Vesta No. 4, which was once the largest bituminous coal mine in the world. To control all means of production, most steel companies also owned the coal companies. The Vesta No. 4 Mine was a subsidiary of the Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation which sent the coal from the Vesta mines down the Monongahela to the Eliza furnace/coke ovens and then to the J&L Pittsburgh Works: King coal, queen coke, and princess steel. Eileen Mountjoy in Ernest: Life in a Mining Town explains that:

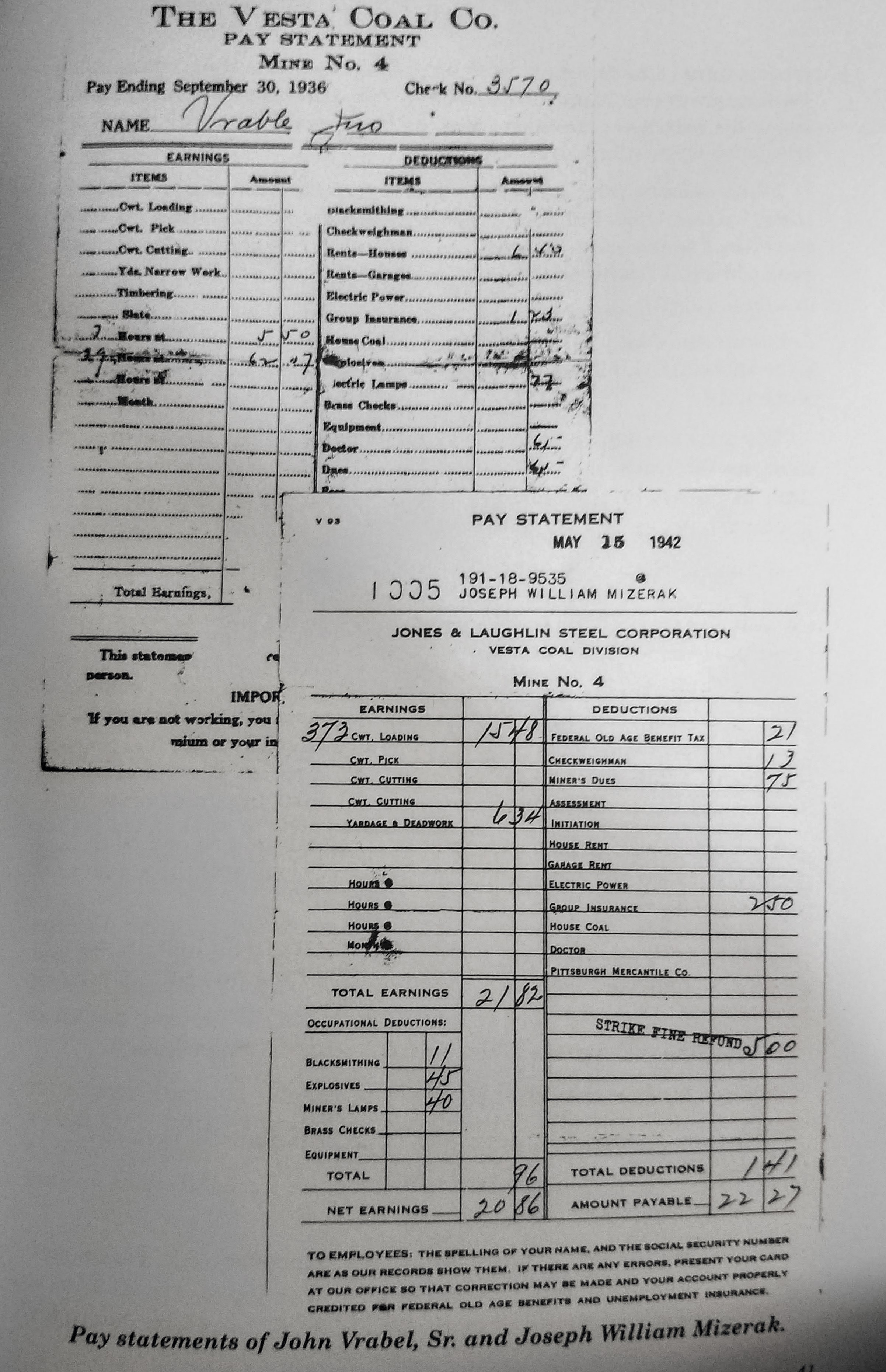

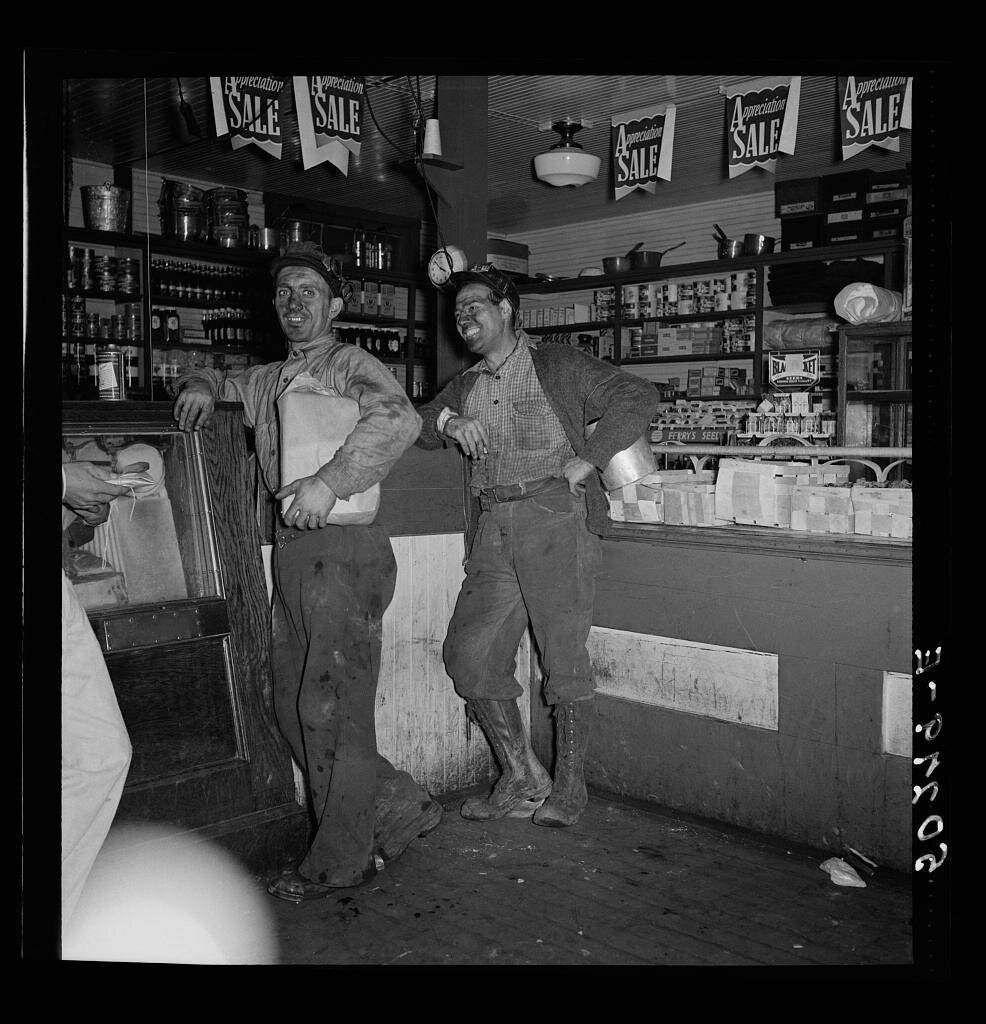

“In 1920, a miner worked hard for his money, and sometimes had little to show for his labor. In those days men dug coal with a pick and shovel and hand-loaded it himself. The company, in 1920, paid thirty-eight cents a ton; on a productive day a man might mine ten tons. At the end of each shift a supervisor, at the tipple, weighed the coal and each miner knew exactly how much money he had earned. Many deductions, however, were taken out of the pay envelopes before miners took them home. In 1925, when a miner earned an average of twenty dollars a week, six dollars each month went for rent on the company house, and a dollar and twenty-five cents for house coal. Three dollars a month were deducted for medical care; this ensured that the miner and his family could see the company doctor as often as necessary. Most of the rest of the paycheck went to the company store, usually before the miner ever had a dollar bill in his wallet.”

In the 1930s, coal production saw a downturn with the Great Depression, and the coalfields experienced some of the highest unemployment and worst poverty rates in Pennsylvania. According to the 1939 census, my great-grandfather’s yearly income was about $1,000 (about $18,000 today). One great-great grandfather was in company house #494 and one was in house #693. According to “Always in a Hole”, “immigrants had no idea that [they] had moved into a community that was among the last remnants of a variation of feudalism in America. Here, Vesta coal company was, to its miners, employer, landlord, storekeeper, and policeman in a system perhaps as repressive as ones immigrants had left behind in their native countries.”

UMWA Poster 1940s Source: Kristen Locy

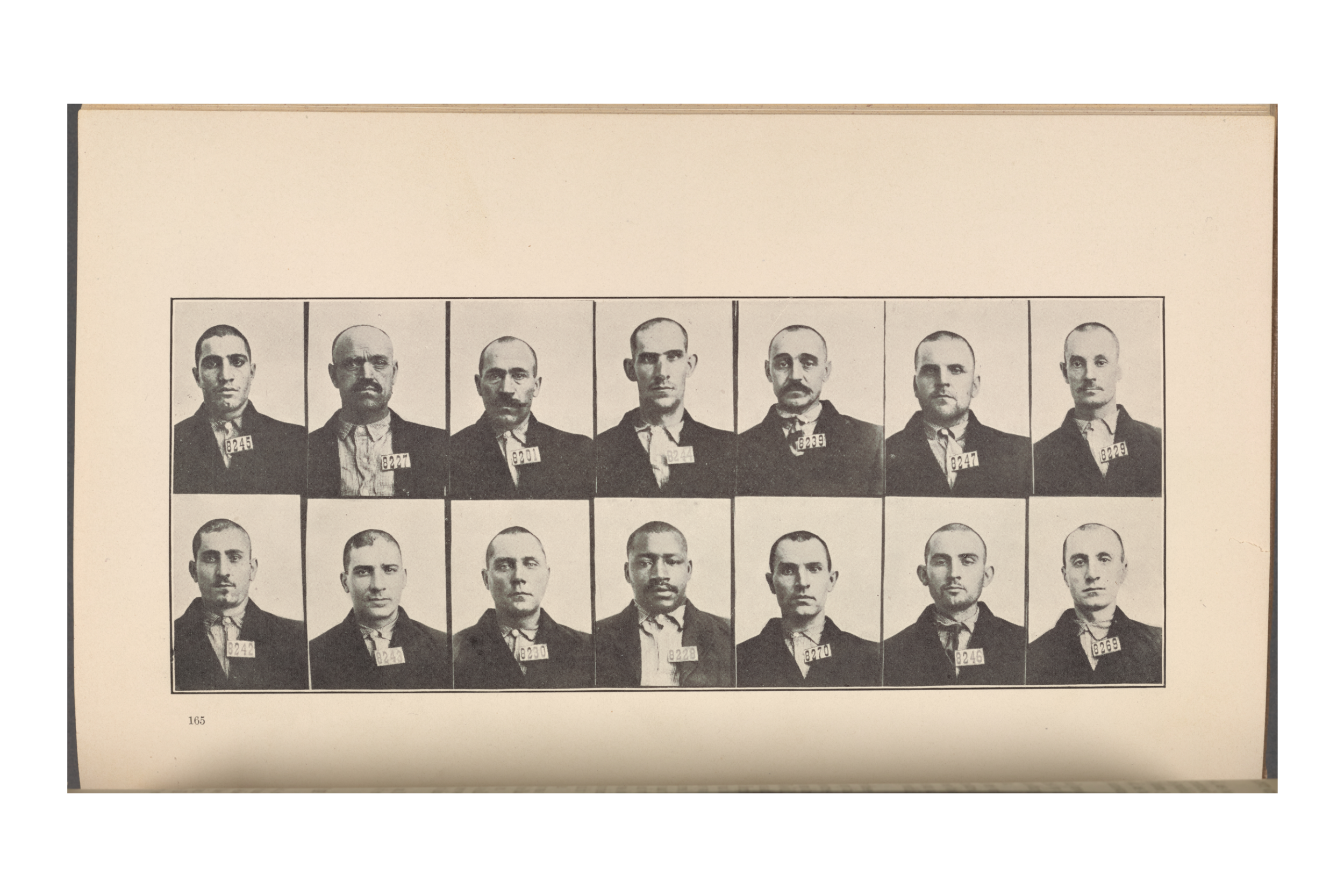

The coalfields and industrial regions of Appalachia have been home to a long history of violent labor disputes and powerful unions. Just up the Monongahela River, the Homestead Strike captured the nation in 1892 as steel strikers battled private security agents, and later, 8,000 members of the state militia, which left 16 dead and scores more injured. This was an inspiring stand against corporate greed for many workers, but at the same time it revealed how difficult it was for a union strike to prevail against powerful government and corporate interests. This battle for workers’ rights against powerful government and corporate interests continues today.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many companies and mines had their own private police force (also the Coal and Iron Police or “yellow dogs”) to keep miners from organizing and to protect company property. Under Pennsylvania law, the governor had the ability to contract policemen; often, police power was “sold” to industrial establishments to keep workers under the control of the company. For especially violent disputes, such as the Homestead Strike, state militias and federal troops would be called in. In 1922 alone, there were about 1,800 strikes in Pennsylvania, including at the Vesta No. 4 mine. Evictions from company housing was always held over the head of striking workers. So was outright violence and war-like tactics. During a 1927 strike at Vesta Mine No. 4, the company built a 14-foot-high fence topped with barbed wire to allow strikebreakers or “scabs” to go to work in the mine during the strike. Labor historian Hoyt Wheeler wrote, “Firing men for union activities, beating and arresting union organizers, increasing wages to stall the union’s organizational drive, and a systematic campaign of terror produced an atmosphere in which violence was inevitable.” This era was marked by violent labor battles and almost unchecked power of the industrial giants as they exploited many of their workers.

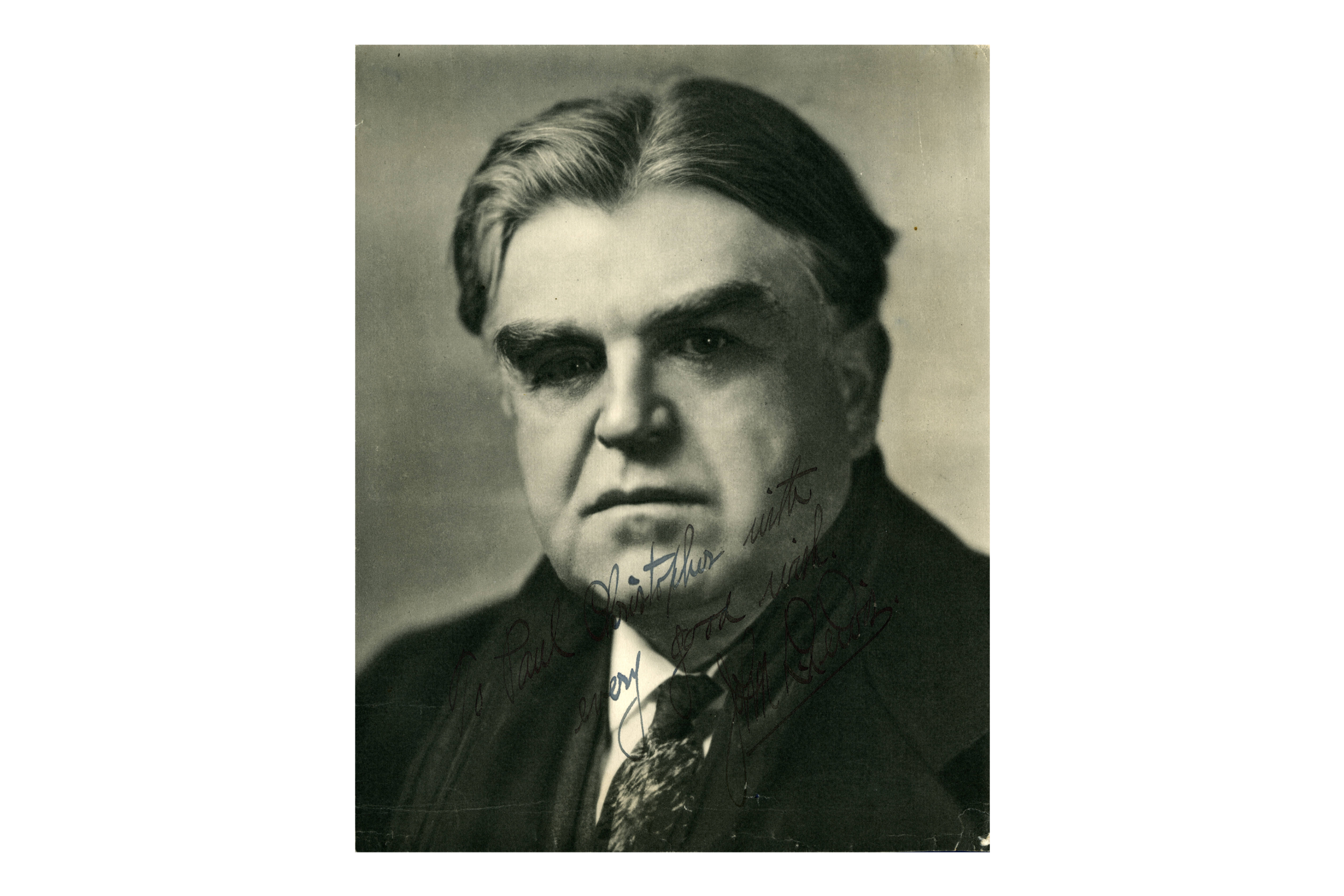

Things started to change in the 1930s with the Great Depression, the New Deal, FDR, and workers turning to pro-labor democratic politicians to solve their labor and economic woes. It was stated in “Always in a Hole” that, “Lewis (president of the United Mine Workers of America) and FDR, both beloved by miners, joined Christ in forming a holy trinity of pictures that adorned the walls of most every house in our village during the turbulent thirties…All coal diggers looked upon FDR as a messiah who would rescue them from the jaws of economic slavery.” In 1933, the National Industrial Recovery Act under the New Deal allowed workers to organize and collectively bargain. A dispute over the Steel Workers Organization Committee organizing at the Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation (also the owner of the Vesta mines) Aliquippa plant made it all the way to the supreme court in 1936. They ruled to uphold the National Labor Relations Act which required businesses to bargain with any union supported by the majority of their employees. In 1937, under Democratic rule, Pennsylvania passed legislation to further protect workers and to abolish the Coal and Iron Police. At Vesta No.4, by the mid 1930s most members from the Independent Workers Brotherhood (the company union) and the National Miners Union had joined the United Workers Union of America (UMWA).

Downturn

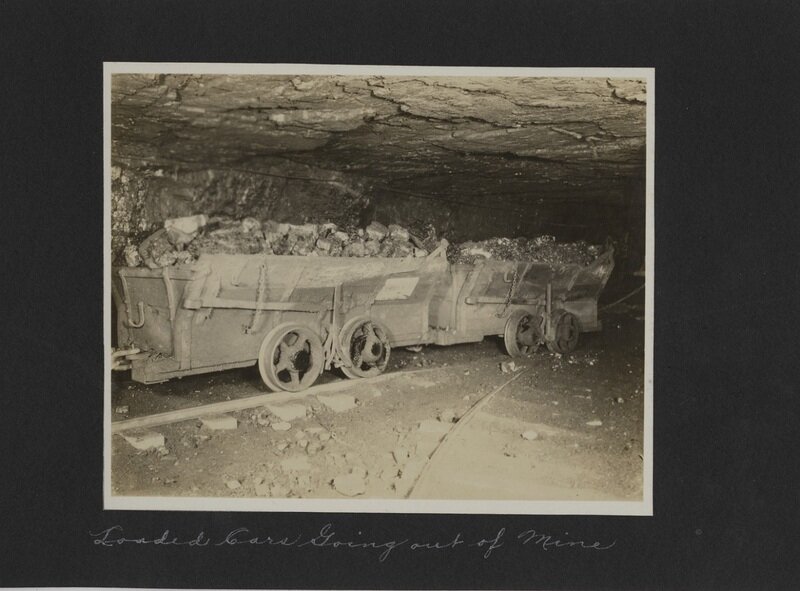

First shift of miners at the Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company Mine #4 near Richlands, VA, 1974

Source: US National Archives

To increase efficiency, steel mills started using oil and natural gas instead of coal for their furnaces. In the 1970s and 1980s the steel mills themselves started shutting down due to modernization and production moving overseas. Besides the Great Depression, Pittsburgh experienced the worst economic downturn in its history. The Vesta Mine closed in 1957, temporarily re-opened in 1960, and permanently closed in 1984. In 1957 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote:

“There will be no jokes in Richeyville on April 1. That’s the day Vesta 4 – the big “picture card” mine, around which the town was built – shuts down. With it goes a $200,000 weekly payroll that fed residents of this community across the Mon River from Brownsville for more than a quarter century. The 900 people are digging in for their greatest battle – that of survival. They are grimly determined not to become a “ghost town,” a fate suffered by other towns in the worked-out bituminous coal belt that slices through Washington, Fayette and Westmoreland Counties. . . A few are old enough to qualify for the United Mine Workers’ union pension of $100 a month which begins at age 60.”

In the 2000s my dad worked at a J&L Steel plant – the company who had also owned the Vesta Mines. Echoing the mines closing in the 1960s, and manufacturing leaving Pittsburgh in the 1970s and 1980s, he was laid off in the Great Recession along with 2 million other workers in manufacturing who lost their jobs between 2007 and 2009. The cycle of boom and bust in the economy of Appalachia has directly affected almost every person in this area.

Not My Great-Grandfather’s Mine Anymore

Mining itself changed from room-and-pillar mining to the more mechanized, efficient, and expansive types of mining such as longwall and mountaintop removal mining. Coal companies needed to access harder to reach coal seams in an increasingly competitive market. These types of mining require less workers, produce more coal more quickly, and due to their scale, ultimately create more environmental disturbance. In West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee, mountaintop removal began in the 1970s as a type of strip mining where the tops and sides of mountains are blasted away to get at underground coal seams and then the waste rock is shoved into valleys and streams. It can be incredibly damaging both environmentally and spiritually for the people who see the mountains that are part of their identity and heritage being destroyed. Since 1976, SkyTruth found that about 1.5 million acres of Central Appalachian forest has been cleared as a result of mountaintop removal mining (see the map below). To put it into perspective, the area of Appalachia ravaged by mountaintop removal is 18% larger than the state of Delaware.

Residents of counties where there has been mountaintop removal are 1.5 times as likely to exhibit symptoms of depression as those of counties without it. Michael Hendryx, author of the 2013 study, states that, ““[The depression] seems to be more about the destruction of the environment. It’s that psychological impact of watching mountains blown up and roads destroyed and communities wither away and jobs disappear and politicians lie to you every day about what they’re doing.” Additionally, according to a 2015 study by the Appalachian Regional Commission, Central Appalachian residents have higher rates of disability and chronic disease than the rest of the nation. In the article, The 100-year capitalist experiment that keeps Appalachia poor, sick, and stuck on coal, Gwynn Guilford explains:

“This may have something to do with the economic precariousness that is a fact of life in central Appalachia. A growing body of scientific evidence links “allostatic load”—basically, chronic wear and tear on the body caused by repeated triggering of stress hormones—with chronic disease and premature death. Many of the maladies strongly associated with allostatic load are problems in central Appalachia, such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Allostatic load is also linked to depression and impaired mental functioning. Some scientists hypothesize that the system’s inability to balance its brain chemistry caused by chronic stress may also encourage addiction.”

Bailey Mine Complex Source: CCJ

About 60 miles south of Pittsburgh, in the beautiful rural area of Greene County, is the largest producing underground coal mine complex in the US, though it has only been operating since the 1980s. Nestled in the rolling hills are roughly 2,000 acres of industrial operations. The Bailey Mine is a longwall mine where huge machines eat up entire seams of coal. After the coal is removed, the land behind the machines subsides. As you drive along the country roads you see conveyor belts sending coal from underground to the Pennsylvania Mining Complex where the coal is processed and loaded into rail cars day-in and day-out. Even though I grew up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, I had no idea it existed until recently, let alone that it is comparable in size to the island of Manhattan. Yet, this isn’t a mine like my great-grandfather’s mine, where he would go underground with a pick and fill carts with coal. This is an incredibly modern major industrial operation with an annual production capacity of 28.5 million tons of coal. Greene County was traditionally a rural area of quiet sheep farms, once the highest producing county in total Merino wool production. It wasn’t until the 1970s that coal mining moved into the region and reshaped people’s identities from farmer to coal miner. As towns in the Pittsburgh coalfields became ghost towns, hit hard by the loss of industry, many residents saw new jobs and new hope for the region as CONSOL moved in.

History Repeats Itself

When one looks at the big picture, it is easy to see that coal hasn’t been a knight in shining armor and brought prosperity to the area. In Greene County, only about half of the population is in the labor force and one in every seven residents live in poverty. Just last February, 370 coal miners lost their jobs as the 4 West Mine closed due to an increasingly competitive market. A coal miner told the World Socialist Web Site (WSWS), “This is going to be devastating, the coal companies just took as much as they can and leaving the people with nothing. These people have families to support, there are no other jobs in the area. The gas companies are doing the same thing. Greene and (neighboring) Fayette County are two of the three poorest counties in Pennsylvania, yet you see gas drilling everywhere. A few people make some money, but most people end up with nothing and now have to drive on even worse roads than they had before because they have been torn up by the gas trucks driving up and down them.” Meanwhile, even though CONSOL claims a record amount of coal production, it was saddled with $908 million dollars in debt in 2017. “They don’t care about the miners,” a miner at the Bailey complex told WSWS, “they’ve already eliminated our health benefits and they are just trying to make as much money as they can. When the company cut the health benefits, some of the older miners were given cash settlements and some were substantial, $75,000 or $100,000. But in reality, that only pays for insurance for four or five years and if you or your wife ends up with cancer or something, that money will be gone very fast.”

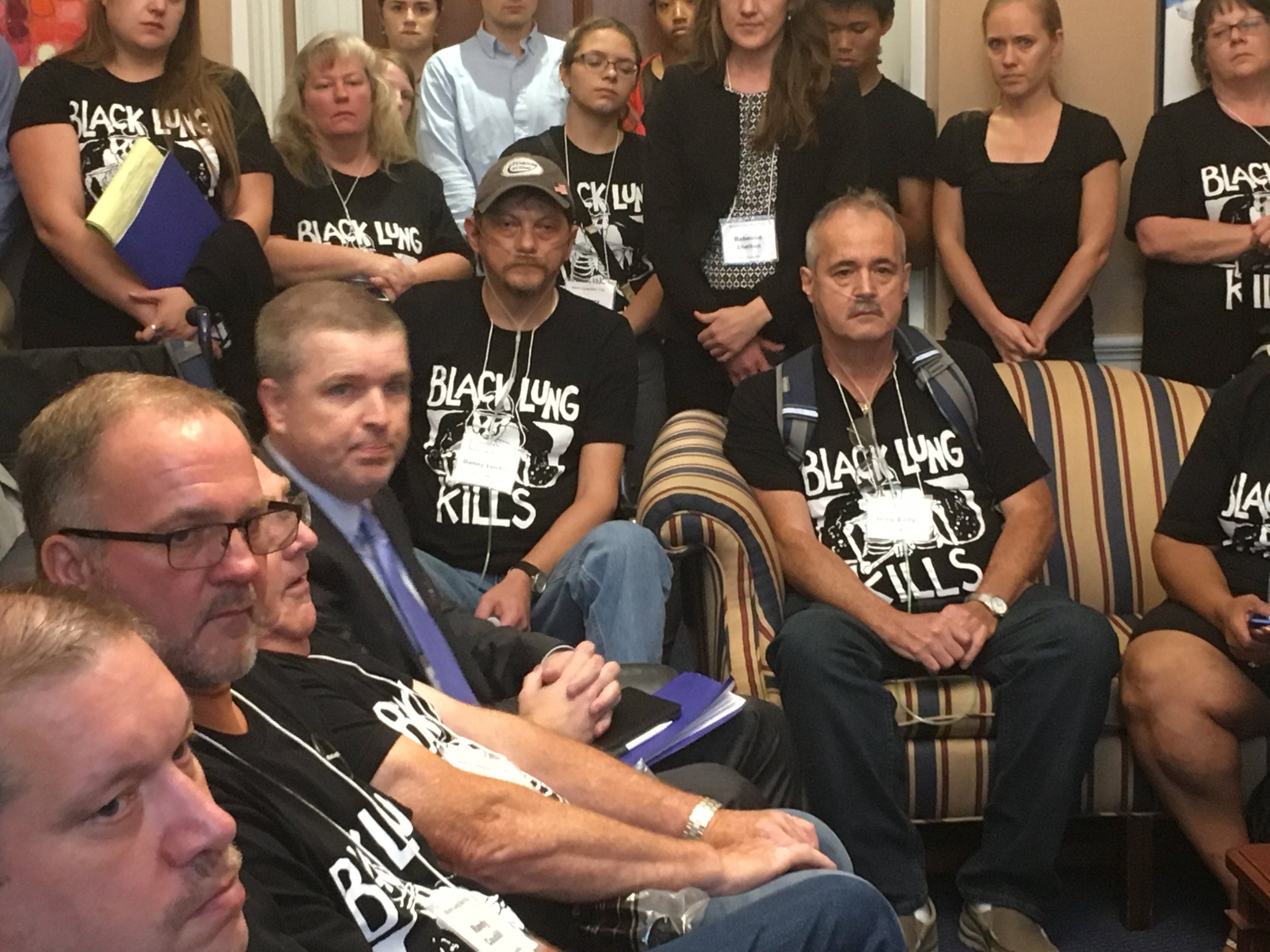

Union membership has declined steadily since the 1970s, and strikes have become harder to win. Large multinational corporations continue to cut back on workers’ rights and benefits such as healthcare, and unions have become less and less powerful and effective. Historian Rebecca Bailey explains, “This fight between collectivism and individualism, the rights of the worker and the rights of the owner, have been part of America since the country’s founding.” The rights miners battled so hard for a century ago are still being fought for today. While the 1930s saw a golden age of the government working to protect labor rights and allow for collective bargaining, eventually the effects of globalization and corporate greed eroded those gains. Chatham University historian Louis Martin explains in the article The Coal Mining Massacre America Forgot, “[Unions] became so dependent on federal labor laws and the National Labor Relations Board that they lived and died by what the federal government would allow them to do. That was the beginning of a decline in union power in this country—one that’s still ongoing.” Martin cites “the failure of the Employee Free Choice Act to pass in Congress (aimed at removing barriers to unionization), the closure of the last union coal mine in Kentucky in 2015, the loss of retirement benefits for former miners, and the surge in black lung disease as evidence of unions’ fading power.”

Despite what the coal companies tout, mining is not necessarily safer than it was 50 years ago. Men are still putting their lives on the line just to make a decent wage in the area they call home. On August 30th of this year, a 25-year old was killed in a Washington County mine when a mine wall collapsed on him. Furthermore, miner’s pneumoconiosis, commonly known as black lung, was on a downturn for decades until recently. Now, an even more severe form of the disease is an epidemic among miners. Epidemiologists at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health say they’ve identified the largest cluster of advanced black lung disease ever reported. Longer work shifts and the mining of thinner coal seams in rock such as sandstone and limestone exposes workers to even more harmful silica dust that leads to their slow suffocation. This is denied by the industry, while they continue to cut their workers’ protection and benefits as they try to turn a profit.

I had naively thought that Pennsylvania’s coal mining identity ended with my grandmother. Since Greene County is so rural and isolated (internet access and cell phone reception are still nonexistent in areas), unless you live there, you can easily turn a blind eye to the destruction. But if you do live there, the mines provide well-paying working-class jobs. Meanwhile, mining companies continue to systematically depopulate the area through buying up land and displacing families. Who cares what happens to the land if no one lives there? In July, the DEP (Department of Environmental Protection) held a public hearing on a coal refuse disposal area (CRDA) and only four people attended (including our community organizer, Nick Hood). Had it not been held at 1 o’clock on a Wednesday, the meeting might have been better attended. This disposal site and related infrastructure will cover 1.4 square miles and essentially fill a valley with toxic sludge. Going back to Michael Hendrix’s study on the effects of environmental destruction on the psyche, for many people it is simply exhausting and depressing to see their home plundered and destroyed while they feel powerless against these powerful companies.

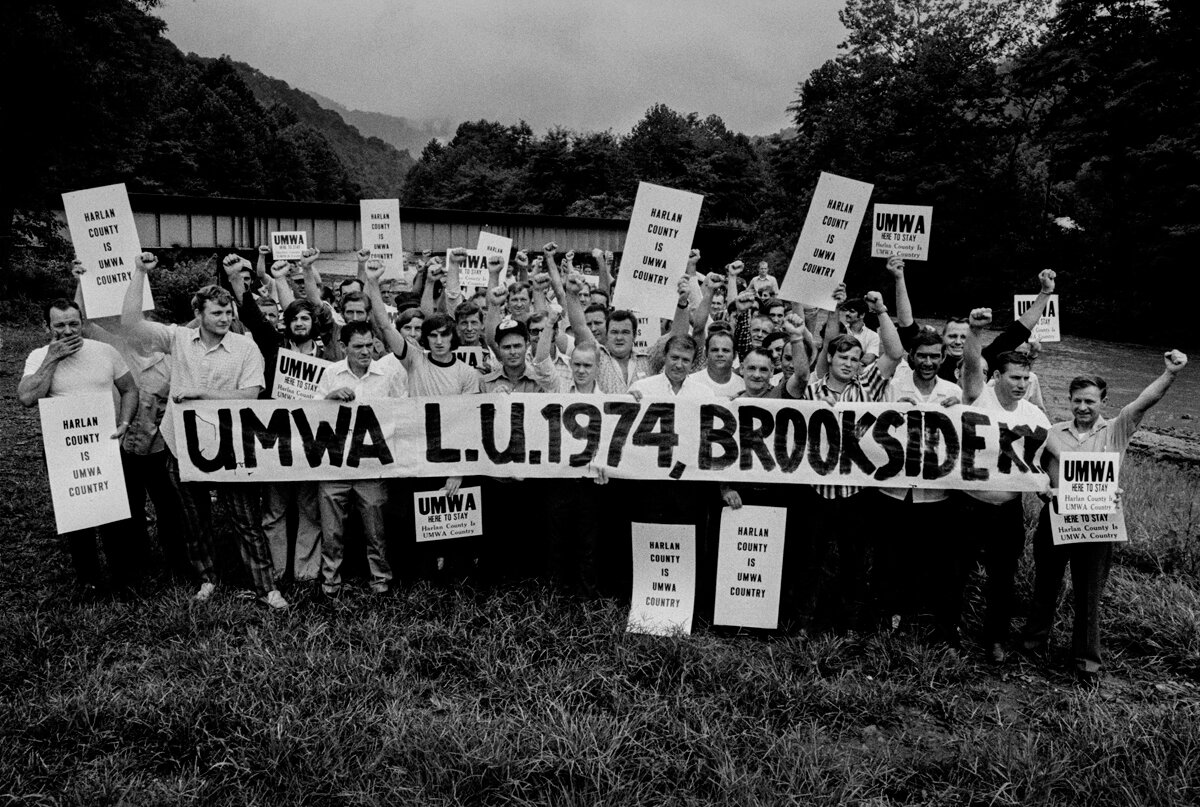

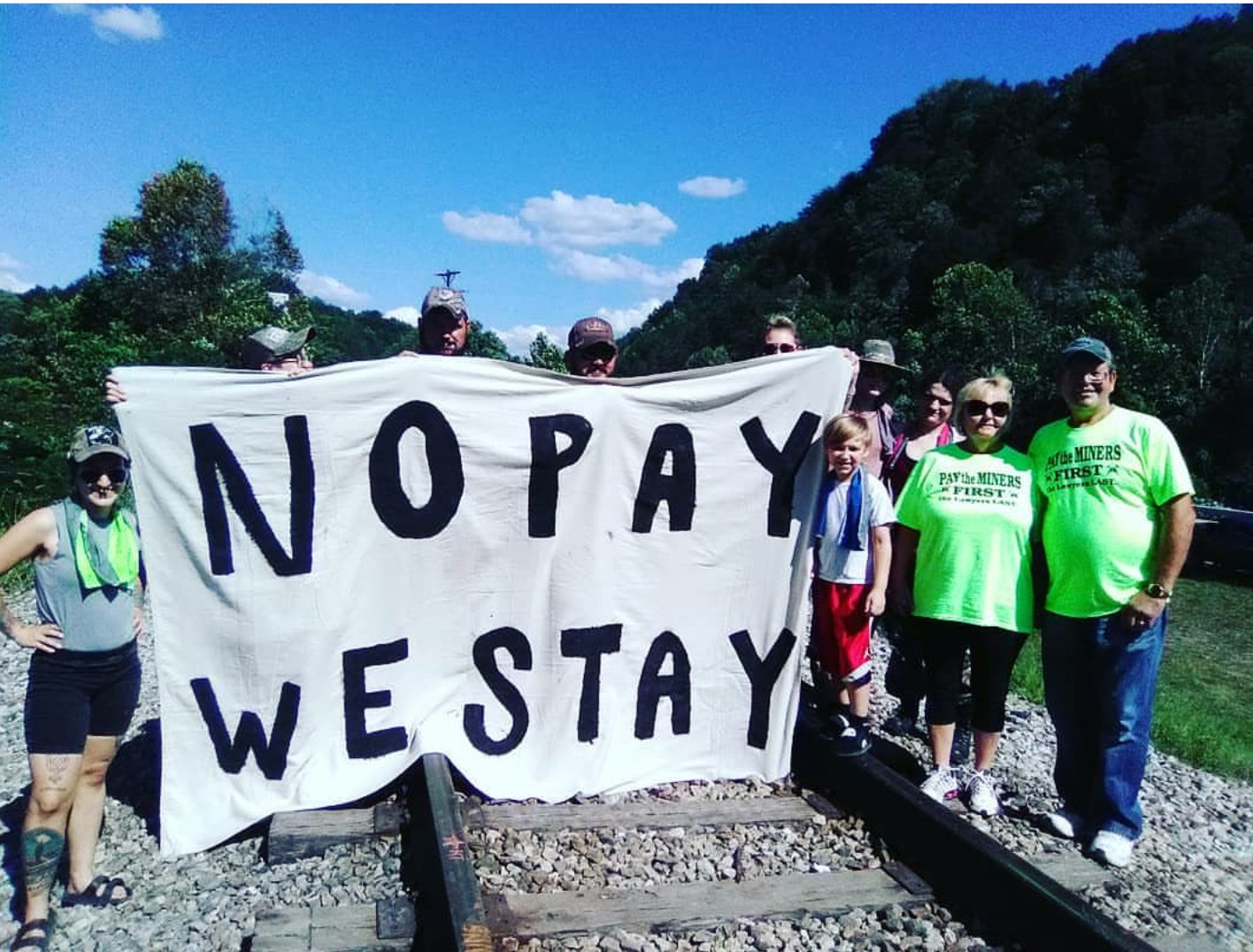

Yet, to say that residents are complacent with this injustice isn’t true. The story of injustice in Appalachia is also one of passionate resistance. Just this past August, coal miners in Harlan County Kentucky protested being laid off without pay by the sixth-largest coal producer in the US – Blackjewel. In the middle of a shift, without warning, Blackjewel told its workers that they were bankrupt and shutting down immediately. These workers soon learned they had not only lost their jobs, but their paychecks as well: the paychecks for their last two weeks of work had bounced. This certainly wouldn’t have been a surprise to Blackjewel. As the company hoped to quietly send out its last rail cars of coal valued at over one million dollars out of the Cloverlick No. 3 Mine in Harlan County, miners decided to block the train and demand the wages they had worked for. Lawyers representing the miners estimated that Blackjewel’s employees in central Appalachia were each owed $4,202.91 on average for wages and benefits earned. Harlan County has a long history of protest and labor wars both in the 1930s and 1970s. The labor unions that the workers fought so hard for no longer exist. Yet almost every generation has a story of having to fight for fair treatment and human rights. A man holding a protest banner told the New York Times, “History’s repeating itself.”

“I’m still fighting. I’m entitled to it. I worked the time. I won’t quit standing til I get it.”

Nimrod Workman was there at the Battle of Blair Mountain. Today, miners are striking again in Harlan County. #NoPayWeStay pic.twitter.com/jAI88yYVaM

— Appalshop (@Appalshop) August 27, 2019

All of these issues – whether it is mistreatment of our workers, systematically destroying our communities, or poisoning our water – are the effect of these major corporations not being held accountable for their actions and taking advantage of oppressed people where they know they can get away with it. It is the story of so many others in America. The families in Flint, Michigan who can’t drink their water. The Navajo who have toxic waste disposed of on their land. The people in Appalachia who have dealt with their land being plundered for fossil fuels for centuries. We all bring our unique histories and stories to the table, but the sooner we realize that we are all fighting for the health, safety, and prosperity of our communities, the sooner we can rise up together against centuries of injustice.

I’m not a coal miner.

But I am inextricably linked to the effects of fossil fuel extraction in Appalachia and the fight for the well-being and future of my community.

Let’s work together against injustice.

A piece of coal from the Cedar Grove seam in Logan County, West Virginia Source: Courtesy of National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center via Smithsonian Institution

Poem written by coal miner Harry Rager in the Vesta No. 6 mine:

Down in the coal mines

Where never shines the light

And all is black and dirty

Dark as darkest night.

We have no light or sunshine

No clear or pure air

Caught up by many dangers

Of which we must beware.

Our backs are bent from toil

Our strength is almost gone

We think “Oh, it’s so useless”

But we toil on and on.

We do not win great riches

In fact we count it luck

If we – with all our toil

Can get a little “chuck.”

Yet there are many people

Who will often say

“The miners are so lucky

They receive big pay.”

Well, just let those people

Just try it once and see

How life and health and sunshine

Are strange to you and me.

It’s not but slavery, comrades,

To mine this precious coal

It takes away your manhood

And it’s tiresome to your soul.

No words of tongue, no words of pen

Can half the picture show

Of the dangers in the coal mines

That the miners undergo.

Source: “Always in a Hole”