Over the past year, CCJ launched our economic justice and diversity work with Greene County residents. We spent most of last year deep in community with the people living across the county, wondering how elected officials are going to improve our economy to increase access to good-paying union jobs and protect our valuable natural resources. As a resident of Greene County, I know how critical the fossil fuel industry has been to the local economy, our tax infrastructure, and our culture. I also know firsthand how the fossil fuel industry has destroyed our access to clean water, systematically depopulated our communities, and corrupted our political system.

Fossil Fuel companies’ control and ownership of political power could not be more evident right now in the conversation about the economic future of Appalachia, particularly western Pennsylvania. All we keep hearing about lately is the need to expand fracking and invest in petrochemical/manufacturing facilities to transition our communities that have been depressed from the declining coal industry. But how good has fracking been for our economy?

Starting in roughly 2010, our region went all-in on fossil fuels and fracking. According to the US Department of Energy, Pennsylvania is the nation’s second-largest natural gas producer and the third-largest coal-producing state in the nation. Meanwhile, West Virginia is the second-largest coal-producing and seventh-largest gas-producing state, and Ohio’s natural gas production grew by 28 times from 2012 to 2018. The results of that strategy are now clear—and they are damning.

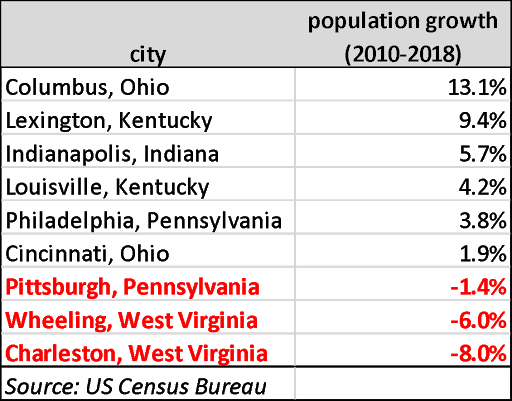

A McKinsey analysis shows a decade of stagnant growth and population decline, in marked contrast to peer cities that pursued other strategies. The truth is that the fracking boom in the Ohio Valley from 2010 and 2018 was also a bust, and it corresponded to an exodus from the region. During that period all eight metropolitan statistical areas in the Ohio Valley lost population.

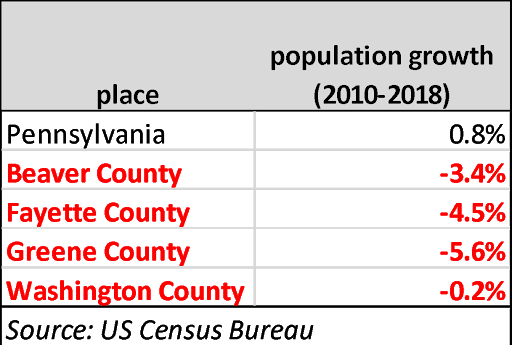

Left: The Utica (yellow) and Marcellus (red) shale formations. The numbers on the right and below are calculated from information provided by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Pennsylvania promoted shale gas development aggressively in rural areas, and yet the southwestern counties at the epicenter of fracking do not show any obvious improvement in well-being. Poverty rates in these counties have remained essentially unchanged for two decades. As the chart below shows, though the overall population of Pennsylvania has increased, the four southwestern counties have actually experienced population decreases.

The fracking boom did not lead to any clear benefits for urban areas either. Despite a glut of shale gas, job losses in manufacturing continued so fast they overwhelmed the addition of extraction and construction jobs. In fact, manufacturing employment in the Pittsburgh area is now at its lowest level in modern history, and possibly ever. The fracking boom even failed to deliver low-cost fuel for local residents: gas for home heating in Pennsylvania is actually about 10% more expensive than the national average.

The results of the Marcellus experiment lines up with the shale gas industry’s long history of over-promising and under-delivering.

Now, the boom is over and the bust is on the way. Wall Street has turned against the industry, especially in Appalachia, and the future looks even more grim. Ohio Valley fracked gas producers performed poorly even relative to the rest of the struggling sector in 2019, and there are storm clouds on the horizon. Chevron was forced to write down its assets by more than $10 billion, with its biggest devaluations coming from its Appalachia shale holdings, including Pennsylvania. In addition to Chevron, CNX Resources, a Washington County-based shale gas company, is writing down $446 million in assets in Central Pennsylvania. The drop means the oil and gas reserves in those areas are no longer considered economic and will not be developed in the near future. In addition, Pittsburgh-based EQT Corp., the largest natural gas producer in the country, is expected to write down between $1.4 billion and $1.8 billion in assets, the company said in a public filing.

It is not surprising that many of the residents we have talked with in Greene County do not see petrochemicals and fracking as the saving grace for our economy. When you dig deeper, you see that though this industry has received so much corporate welfare, it is still struggling to hang on. One independent analysis found that Pennsylvania provided a minimum of $3.2 billion in fossil fuels subsidies during the fiscal year 2012-2013. What might be the most high-profile state subsidy was a $1.6 billion tax break for Shell to build a petrochemical facility in Beaver County. The giveaway is equivalent to $2.6 million for each of the possible 600 permanent jobs at the plant—a staggering gift to a company that registered more than $21 billion in profits in 2018. Just this past week our state legislative body passed HB 1100 which could provide hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded subsidies to incentivize the building of more chemical and plastic factories in PA.

Last year, Greene County released a marketing plan that basically tells the fossil fuel companies that the county will give them whatever they want. From these financial analyses of this industry, it is clear they cannot survive without public handouts. Is it really in the best interest of the public to invest in a private industry that is already busting? Just imagine how those billions of dollars could create healthy jobs by reclaiming the legacy cost of energy extraction, investing in improving our education and healthcare systems, and updating our infrastructure across the state.

This year it is our time to speak out against corporate handouts and force our government to invest in solutions that don’t jeopardize our survival, solutions that actually transition our hometowns into thriving communities. When we all come together and work collectively, we do have the power to create an economic future that is sustainable and not rooted in yet another boom and bust industry.